The Pavilion at Hyde Park

Grand Old Houses takes you on a tour of the Pavilion at the Vanderbilt Mansion at Hyde Park

The Vanderbilt Pavilion at Hyde Park

The Pavilion

The Pavilion at Hyde Park was the first new structure erected at Hyde Park shortly after the Vanderbilts purchased the property in May 1895 for $125,000. It was designed by McKim, Mead, and White, the same architects who designed the main house, and was erected by Norcross Brothers in 66 working days, from September 8, 1895 to November 24, 1895, on the site of the old Langdon carriage house. The cost of the Pavilion was roughly $50,000.

The Pavilion was intended as a playhouse (also referred to as a sporting pavilion or casino — a term borrowed from the Renaissance meaning “pleasure house”) for the Vanderbilt’s at Hyde Park. Though modest compared to playhouses for other stately homes, the Vanderbilts’ Pavilion was conceived in the same tradition. It was located in close proximity to the outdoor grass tennis lawn and featured a shower room.

As the design and construction of the main house took nearly four years to complete, the Vanderbilt’s used the Pavilion as their primary residence at Hyde Park until the main house was completed in April 1899. At the end of that month, furniture was moved into the completed mansion, where on May 12, 1899, the Vanderbilts held their first house party. From that time, the Pavilion functioned as a playhouse and bachelors lodge. On occasion, the Vanderbilts stayed at the Pavilion on weekends in the winter season when the main house was “put to bed” for the season.

The Pavilion at Hyde Park when completed in 1896 (before the enclosure of the veranda with glazed panels which was completed by 1909).

Photograph courtesy of the National Park Service

The Exterior

The pavilion represents an compact adaption of classic Greek architecture and is situated solidly on the landscape. It is composed of symmetrical east and west facades with centered projecting porticos supported by Doric columns. An open veranda was placed on the south elevation to balance the north and south wings. By 1909, the veranda was enclosed with glazed panels to create a sun room. At the top of the Pavilion, the four gabled sides are united by a shingled attic surmounted by a balustrade.

The exterior walls are finished in a rough course plaster called roughcast or pebbledash (lime mixed with cement, sand, small shells, and pebbles) and received a surface coating of limewash, a mixture of lime putty and water. Interestingly, Stanford White employed pebble dash as a wall treatment at Boxwood, his own home on Long Island built about the same time as the Vanderbilt Pavilion.

Certain liberties have been taken in the interest of functional arrangement, such as the placement of window openings and modifications necessary for the captain's walk on the roof.

The Interior

Even the interior decoration inside the Pavilion symbolically perpetuated the idea of a sporting life. The main space was a two-story hall, paneled in oak at the first story level and surrounded by an open balcony on the second story. A large fireplace dominates the center of the south wall. A large 32-light brass chandelier is suspended from the ceiling beneath a circular laylight. Large mounted trophies of elk, buffalo and a ram decorate the walls. The room has the overall feel of the gentlemen’s lodges of the late nineteenth century.

Surrounding the central hall, the first floor included a living room, bedroom, kitchen, scullery, pantry, a bath room, and shower room. A staircase hall on the north side of the hall provided access to six bedrooms (three of these for servants), a linen closet, a bath room, and lavatory. An additional bath room, likely for use by the servants, was located in the basement.

The Pavilion Today

Today, the Pavilion is used as the Visitor Center for the Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Park.

In 2015, a capital improvement project addressed the roof, chimneys, feature windows, and the skylight. In 2022, another capital project restored the badly deteriorated "Captain's Walk" roof balustrade, replaced missing shutters, stabilized and repair the porch columns, and addressed the damaged and missing areas of pebble dash stucco siding. The wood trim received a fresh coat of paint and the pebble dash stucco received a protective, breathable lime-wash coating.

View of the Visitor Center at the Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Park.

Photograph by David W. Haas, August/September 1999, courtesy of the Historic American Engineering Record at the Library of Congress

Historic: The Vanderbilt’s Hyde Park

Grand Old Houses takes you on a tour of the historic Vanderbilt Mansion at Hyde Park

Hyde Park from the lawn

Photograph by David W. Haas, August/September 1999, Historic American Engineering Record at the Library of Congress

In a previous article, I shared a number of present day photos of Hyde Park, otherwise known as the Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site, which capture how the National Park Service has been a great steward of this historic property. However, for a number of reasons, not least of which is to protect the fragile treasures within, visitors are prevented from truly getting inside these spaces.

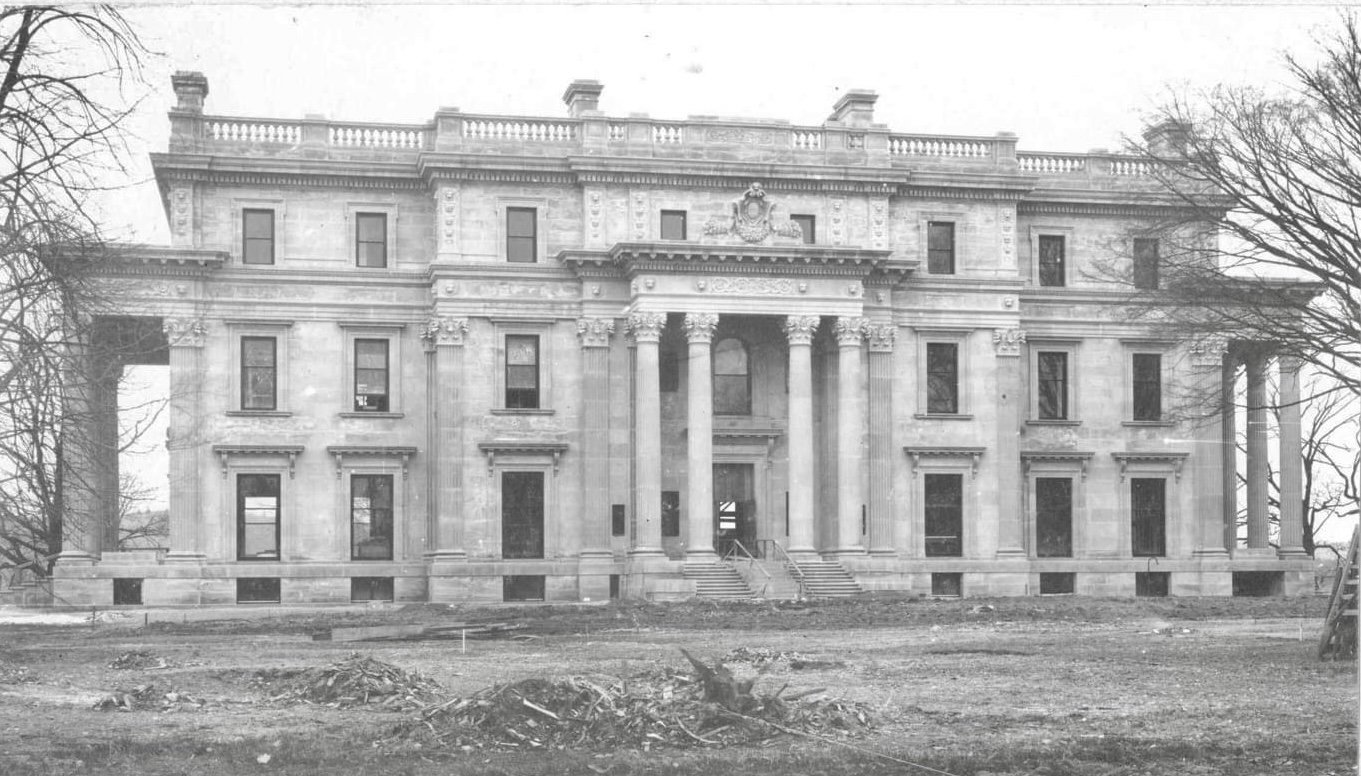

Photograph of Hyde Park under construction, ca. 1898

Courtesy of the National Park Service

The Estate History (abridged)

In May 1895, Frederick William Vanderbilt and his wife, Louise “Lulu” Holmes (née Anthony), purchased the Langdon estate at Hyde Park for $125,000, comprised of a main house and scattered outbuildings, 153 acre park, and a 459 acre farm on the east side of the Post Road. The Langdon estate had previously been acquired by John Jacob Astor in 1840 for $42,000 as a country place for his daughter, Dorothea (née Astor), and son-in-law, Walter Langdon, and their five children. After an 1845 fire destroyed the existing house, the Langdons soon reconstructed another on the original site. After Walter died in the house in 1847, Dorothea left America, permanently settling in Europe by 1852, the year she gave (or perhaps sold) the house to her son, Walter Langdon, Jr. and his wife, Catherine Ludlow (née Livingston). Like later owners Frederick and Louise, they left no children and owned the house until their deaths, Catherine in 1883 and Walter Jr. in 1894.

After the Vanderbilts acquired the property, they attempted to update the existing picturesque Langdon House, however, the 1840s house proved structurally unsound, so they hired Beaux-Arts architect Charles F. McKim, of McKim, Mead, and White, to design a new house on the original site. McKim’s partner Stanford White, who was known as the artistic leader of the firm, assisted as an antiques buyer. The house, which has been described as a Beaux-Arts interpretation of the Italian Renaissance, was built with Indiana limestone and features large Greek ionic porticos on all four sides.

As the grounds were part of country estates owned by influential and wealthy families for nearly two centuries, the specimen trees which they planted may be ranked as a feature of interest second only to the house itself. More than 40 species and varieties are represented, many of them from Europe and Asia, including European ash, European beech, English elm, Norway spruce, Norway maple, the red-leaved Japanese maple, and a ginkgo, or Chinese maidenhair-tree. This ginkgo is among the largest of that species in the United States. Among the native American trees represented are sugar maple, flowering dogwood, eastern hemlock, Kentucky coffeetree, white oak, black oak, eastern white pine, and blue spruce. Other examples of their kind include large beeches, bur oak, and a great cucumber magnolia.

There are also extensive Italian Gardens, which lay south of the house, and date back as far back as 1795. Landscape architect James L. Greenleaf radically revised and enlarged the gardens between 1902 and 1903 for the Vanderbilts. The gardens, which incorporate several periods of development, were divided into three units: The greenhouse gardens, the cherry walk and pool gardens, and the rose garden. The first of these consisted of three separate parterre gardens within a rectangle framed on the west by the rose and palm houses and on the north by the tool house, carnation house, and gardener's cottage. The cherry walk and pool gardens, were located east of this group at a lower level, and progressed from the pergola to the garden house. The rose garden, still further east, had two terraces and contained panel beds.

Inside Hyde Park

The resulting 54-room house has a classic Beaux-Arts plan, with the major public rooms on its ground floor – the central Entrance Hall, Dining Room, and Living Room – all in one line, parallel to the Hudson River. North and South Foyers provide transitional space from the Hall to the Dining Room and Living Room. Five secondary spaces are located off the elliptical Entrance Hall: the Lobby, Den, Gold Room, Grand Staircase, and Lavatory.

First Floor

Courtesy National Park Service

The second floor rooms, comprising Mrs. Vanderbilt's suite of Bedroom, Boudoir and Bathroom (designed by Ogden Codman), Mr. Vanderbilt's Bedroom and Bathroom, Guest Bedrooms and Baths and the Linen Room, are disposed around the Second Floor Hall and the North and South Foyers. The third floor contains five additional guest bedrooms, and a Servants' Hall separated from the guests' rooms by a door at the main staircase. Supported by both concrete and steel, the Vanderbilt mansion was considered modern for its time. The mansion also included plumbing and forced hot air central heating and electric lighting which was powered by a hydroelectric plant built on the estate on the Crum Elbow stream.

Second Floor

Courtesy National Park Service

At least four fully fledged decorating firms were independently, and simultaneously, at work on the design and execution of Vanderbilt’s interiors under the general supervision of McKim and the clients. The firms were: Ogden Codman, A. H. Davenport, Georges A. Glaenzer, and Herter Brothers. The Vanderbilts gave McKim overall carte blanche on the design and furnishing of the ground floor reception rooms. Following an on-site conversation with McKim, Vanderbilt provided $50,000 at the disposal of Stanford White, excluding duty and freight charges, to spend on articles of furniture, preferably “old Italian,” and architectural salvage during an upcoming trip to Europe. Furnishing plans were provided for the hall, staircase, reception room, lobbies, dining room, living room and porticoes. In execution, the concept was followed with remarkable diligence. Herter Brothers would carry out the architectural decoration of the entrance vestibule, the elliptical hall and the dining room and A. H. Davenport, the living room. The balance of the ground floor was consigned to the French-born New York furniture dealer-decorator Georges Glaenzer.

In 1906, seven years after the house was completed, however, the Vanderbilts engaged New York architect Whitney Warren, of Warren & Wetmore, to redesign certain elements of the house. Warren, a close friend of his brother, William K. Vanderbilt, had recently taken over the design of Grand Central Station from Reed and Stem. In his redesign, he directed changes in the Entrance Hall and the Drawing Room, where he had the Harry Siddons Mowbray mural covered up (which the Vanderbilts did not like). On the second floor, he removed the coved laylight atop the second story and replaced it with a flat frosted glass laylight. The wood balustrade around the elliptical opening on the second floor was removed and replaced by a cast-stone balustrade. A deep plaster cove, embellished with lattice-work panels and oval medallions with female figures, was added to the ceiling of the second floor beneath the new laylight.

First Floor Rooms

Entrance Hall

The Entrance Hall provides immediate access to all of the principal rooms on the first floor. The elliptical room, though formal in appearance, functioned both as a living hall, used for informal gatherings, as well as circulation space, typical of classical French design. The room was furnished with tall palms, animal skin rugs, and comfortable couches, allowing for informal use where the Vanderbilts and their guests would sit down and fall asleep in front of a big fire.

The Hall is anchored by architectural features at each compass point—the main entrance centered on the east side, with a fireplace and mantel directly opposite on the west side. Located at the north and south ends of the ellipse, foyers connect the Hall with the Living Room and Dining Room. Angled alcoves flanking the fireplace provide access to the West Portico. Additional doorways open to adjoining rooms and the Grand Staircase. The walls are articulated with green marble pilasters with white marble bases and capitals. The ceiling reveals the second floor with an elongated octagonal opening encircled by a massive double balustrade, allowing natural light to flood the Hall from the laylight and skylight above.

Courtesy of the National Park Service

Drawing Room

The Drawing Room (also called the Living Room) extends across the entire south end of the first floor. The wide, recessed doorway, flanked with antique Cippolino marble columns and fitted with large sliding pocket doors, connects the room to the South Foyer and the Hall beyond. Directly across the room is a wide doorway flanked by smaller doors leading to the South Portico. The composition of the ceiling visually divides the room into three bays, the effect enhanced by a pair of marble fireplaces and the arrangement of furniture into distinctive areas. The walls are paneled in Circassian walnut and the twin fireplaces are Italian marble.

Two large tapestries flanking the doorway are from a series depicting episodes of the Trojan War (the others from the set hang in the South Foyer). The east and west walls feature a pair of late 16th- or early 17th-century Italian armorial tapestries bearing the Medici family coat of arms. The room is furnished with a combination of antique Renaissance furnishings and Louis XV style seating. As it appears today, the room represents the design of Whitney Warren, who redecorated the room in 1906. The original ceiling mural by H. Siddon Mowbray was removed at that time.

Following dinner, men would remain in the Dining Room (or head to the Library) for cigars, while the ladies would retire to the Drawing Room for coffee and liquors. The men would later join them for games of cards, charades, and music.

Dining Room

The Dining Room extends across the entire north end of the first floor. Measuring 50 feet by 30 feet, the room is grand and spacious. The walls are finished with parcel-gilt full-height walnut paneling, rising to a 17th-century coffered ceiling salvaged from an Italian palazzo. The large stone fireplaces are from Paris and Florence. Carved in the 16th century, one illustrates scenes from the Judgement of Paris, and the other bears the Medici family coat of arms. The extension table at the center of the room seats up to eighteen.

The most important furnishing in the dining room is the large carpet—a rare Persian carpet — one of the largest Islamic carpets in existence measuring nearly 20 feet by 40 feet. Thought to be nearly 400 years old, this carpet was the single most valuable object in the house at the time it was installed, and likely remains so today.

The central panel of the ceiling was commissioned from the American artist Edward Simmons, who trained in Paris and was a leading figure of the American Impressionist movement. His surviving murals include those in the New York Supreme Court, the Waldorf Astoria New York, and the Library of Congress in Washington, DC.

Reception Room

Following her sister-in-law Alva Vanderbilt’s example, Louise installed an eighteenth-century-style French salon in the house known as the Reception Room (or the Gold Room). McKim had asked Stanford White in September 1897 to “Look up old room in Paris Style Louis XVI, and if you find anything worth while, cable,” for Hyde Park. While White was unable to produce the antique paneling, their decorator, Georges Glaenzer, recreated a richly-paneled Louis XV-style room inspired by French design sources.

The Reception Room, however, was used very little. Tea might be served there for very special guests during a weekend visit—or a small group of eight to ten dinner guests would congregate there until dinner was announced. It was more often used by Louise when she wanted to be alone, as a former butler explained that “when the door was closed that was a sure indication that Mrs. Vanderbilt did not want to be disturbed.”

Office

Vanderbilt’s office was off the Entrance Hall and directly next to the front door. The woodwork is Santo Domingo mahogany. Plates on the wall are Chinese, and a painting by the French artist, Lesrel, hangs over the desk. Above the fireplace, early Italian and Spanish flintlock pistols are grouped about an old Flemish clock. A hand carved Renaissance panel forms the back of the desk chair.

In the bookcase are about 400 volumes, mostly fiction and travel. Included among these are the college textbooks that Frederick used at Yale. From this room Vanderbilt conducted his estate affairs, such as tree culture and the operation of the greenhouses, gardens, and his dairy and stock farm across the road.

Library

The Library, sometimes called the Den, was also decorated by Georges Glaenzer. Swiss artists were brought to America to create the hand-carved wood on the walls. A vaulted section of the ceiling is molded plaster, made to simulate carved wood. The carved mantel of the fireplace reportedly from a European church. A porcelain clock-and-candelabra set on the mantel was a gift from Louise's mother. Guns on the wall opposite the fireplace are antique Swiss wheel locks. More than 900 volumes on history, literature, natural science, and other subjects fill the bookcases in the room. The Library was used as the family living room. In the afternoon, they gathered for tea there.

Grand Staircase

The Grand Staircase, featuring sweeping wrought iron balustrade, begins with ten steps leading up to a landing along the west wall, followed by another ten steps to an east-facing landing, then ten more steps heading west to a third landing, and, lastly, nine steps east to reach the second floor. On the wall opposite the foot of the stairway is an 18th-century Flemish tapestry. The floor in the lower-stair hall is old Italian marble. A chair and marble fernery are Italian, and a large Chinese bowl of the Ming Dynasty is about 500 years old.

Italian busts and statues occupy niches along the way including marble sculptures depicting the infant Hercules (strangling one of the snakes sent by the goddess Hera to kill him in his cradle), Eros, Psyche, along with Persephone (Greek goddess of spring and queen of the underworld). At one of the landings is a painting by the French artist, Adrien Moreau. An early 18th-century Beauvais tapestry hangs on the second-floor wall.

Courtesy of the National Park Service

Second and Third Floor Rooms

Second Floor Hall

In 1906, architect Whitney Warren installed the balustrade which now overlooks the reception hall. In the hall, there are three 18th-century Flemish tapestries, two Italian fringed and embroidered hangings draped over the balustrade, and two sets of matched high-backed chairs in walnut— one set of six chairs, one of four. A teakwood cabinet is of Chinese design.

View the the Second Floor Hall facing the Vanderbilt’s rooms

North and South Foyer

In the North Foyer, on a Louis XVI table stands an incense burner fashioned of marble and cloisonne. Overhead is a chandelier of beaded crystal; one of similar design is in the south foyer. Hanging here are original paintings by the 19th-century artists, Schreyer, Bougereau, and Villegas. Vanderbilt was more noted for the fine tapestries he collected than for outstanding paintings.

The South Foyer leads to the master bedrooms. French doors can be closed to separate this wing from the rest of the second floor. In the foyer are paintings by Kellar-Reutlingen and Firman-Girard.

Mrs. Vanderbilt's Room

Mrs. Vanderbilt's suite of rooms are decorated in the Louis XV style, with references to some of the finest rooms created in eighteenth-century France. The railing around the bed is borrowed from an architectural convention typically found in royal bed chambers. For the architecture of the room, Ogden Codman relied on 18th-century architectural platebooks by Jacques-François Blondel and Alexandre Eugene Prignot. The British art dealer, Joseph Duveen, procured the 15 painted vignettes—copies after Charles-Joseph Natoire and Francois Boucher.

The heavily napped rug was made especially for this room and weighs 2,300 pounds.

Notable furnishings from the workshop of French ébéniste Paul Sormani fill the room, including a curvaceous commode in the Louis XV style made about 1875. The floral inlay and marquetry, and the gilt bronze mounts are indicative of Sormani's ability to create a impressive furniture in the style of the furniture made for French royalty.

Adjoining the bedroom is the boudoir, furnished in the same motif. Notable pieces include a Dresden chandelier-and candelabra set.

Mr. Vanderbilt’s Room

Georges Glaenzer also contributed to Frederick’s bedroom on the second floor. The room has carved woodwork of Circassian walnut. The bed and dresser were designed as part of the woodwork and were installed by Norcross Brothers. Although later slightly modified by the Herter Brothers, the bedroom as designed by Glaenzer featured Verdure tapestry wall hangings. The walls and doors are covered with 17th-century Flemish tapestry. Hand-painted designs on the silk lampshades match those on the Chinese bases. The fireplace has a large carved mantel. On the floors are dark-red rugs made in India.

Much of the French classical bedroom furniture in Hyde Park, thought to have been supplied by Glaenzer, might be from his subcontractor, A.H. Davenport, rather than French sources. The suites bear close resemblance to the Davenport-supplied French Louis XV and Louis XVI style bedroom suites ordered by Ogden Codman for Frederick’s elder brother, Cornelius Vanderbilt II, at The Breakers in Newport and now known to have been primarily manufactured by Davenport.

Courtesy of the National Park Service

Guest Rooms

The Blue Room is the largest of the guest rooms. Mrs. Vanderbilt’s niece, Margaret “Daisy” Louise (née Post) Van Alen, used this room during her visits to the Vanderbilts. The windows of this room give a sprawling view of the Hudson and the mountains beyond. A white onyx French clock and companion pieces adorn the mantel, and a rare old (Ghiordes) prayer rug is spread before the fireplace.

In the Mavuve Room, most of the furnishings are of French design. In the center of the room is a finely woven Persian dower rug. Pieces on the mantel are of the French Empire period.

The Red Rooms open onto the second floor hall and are connected by a doorway to form a two-room suite. As with the other guest rooms, the furnishings are in the French style. A frieze on a Greek subject embellishes the 18th-century English Georgian mantel in the larger room.

Common to all guestrooms is the 18th-century French style of furniture and the use of a distinct color scheme. The guestrooms are believed to reflect the design of Ogden Codman Jr. Each guestroom has a bath and one or more closets. The bathroom accessories always matched the color scheme of the guestroom.

Third Floor Rooms

On the third floor, there are five further guest rooms, separated from the servant's hall and their quarters. The third floor guestrooms are as elaborate as any on the second floor and consist of the Pink Room, with white painted furniture—often used by Vanderbilt in the winter; the Little Mauve Room, furnished with oak furniture; the Empire Room, with French Empire period furniture and satin-covered walls to match the covering on the furniture and bed; and the White Room, with white furniture, drapes, and upholstery. When the nine guestrooms in the house could not accommodate everyone present, the pavilion was used as a guesthouse.

End of the Vanderbilt Era

After Louise’s death in 1926, Frederick became a virtual recluse; living with the servants on the third floor until his death in the home in June 1938. Reportedly the only Vanderbilt of his generation to increase his inheritance to a sizable fortune, he was a director of 22 railroads at the time of his death, including the New York Central, his family’s primary source of wealth, where he had been a director for 61 years.

Like the Langdon’s before them, the Vanderbilt’s left no children to inherit their estate, so Frederick left Hyde Park (amongst others) and $10 million to his wife's niece, Margaret “Daisy” Louise (née Post) Van Alen, the widow of James Laurens Van Alen (a grandson of The Mrs. Astor) who later married yachtsman Louis Bruguière. Having no need for Hyde Park, she put it on the market, but in the midst of the depression, there were no takers.

Vanderbilt’s neighbor down the Hudson River, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, became interested in preserving the estate, citing its collection of trees, and his influence was a major factor in having the park portion of the estate, including the house (together with most of its original furnishings), donated and transferred to the National Park Service by Van Alen. The acquisition was approved in 1939, and in July 1940, the property was opened to the public under its current name, the Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site.

Courtesy of the National Park Service

The Vanderbilts at Hyde Park

Grand Old Houses takes you on a tour of the present day Vanderbilt Mansion at Hyde Park

View of the Hudson River from Hyde Park

I despise the word mansion.

It unnecessarily creates a gulf between the visitor and the building that leads to an us vs. them mentality. When I use the word to describe a house, people are quick to write in with negative comments, criticizing virtually every aspect of the building. The houses get described as cold, austere, and “cheerless formal piles.” Just by using the word mansion, people immediately feel emboldened to dismiss the house and the people who lived there as impossibly distant and, very likely, severely unhappy. While many of these houses were built by sordid robber barons and ruthless industrialists, they were, nevertheless, family homes where people had friends over for dinner, listened to music together, and played games.

There is plenty to discuss about the business practices of the late 19th century (and today), but what has always drawn me to historic homes is far simpler. These private homes, whether intentional or not, reveal a great deal about the people who built and inhabited them. Everything from their location (de rigueur Newport or haughty Hudson Valley gentry) and choice of architect (gothic A.J. Davis or organic Frank Lloyd Wright) to the style of their staircase (closed in a corner or romantically heart-shaped) tells us something important about how these people wanted to craft their everyday lives.

Which brings us to the Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site, commonly called the Vanderbilt Mansion. This house, however, was simply called Hyde Park by Frederick William Vanderbilt, the man who built it along the Hudson River in the 1890s. Vanderbilt was a grandson of the legendary Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, and lived here with his wife, Louise “Lulu” Holmes (née Anthony), the divorced former wife of Frederick’s first cousin, Alfred Torrance. Frederick W. Vanderbilt was the third son of William Henry Vanderbilt (primary heir of the Commodore), and an 1878 graduate of Yale, earning him the distinction of being the only one in his family to graduate from college.

Unequivocally a mansion by any reasonable definition, the roughly 45,000-square-foot country house also has the distinction of being known as the smallest of Frederick’s generation of Vanderbilt houses (see: Biltmore, The Breakers, Florham, Idle Hour, Elm Court, etc.). While Frederick and Louise bought and sold a number of other city and country houses, they kept Hyde Park until their death.

While some see a building more suited for institutional purposes, say a court house or an elaborate town hall, I see it as a home for a couple who wanted to honor the history of the location, the buildings that came before it, and create a family home that allowed them to entertain their closes friends and family on an intimate scale.

The Estate History (abridged)

In May 1895, Vanderbilt purchased the Langdon estate at Hyde Park for $125,000, comprised of a main house and scattered outbuildings, 153 acre park, and a 459 acre farm on the east side of the Post Road. The Langdon estate had previously been acquired by John Jacob Astor in 1840 for $42,000 as a country place for his daughter, Dorothea (née Astor), and son-in-law, Walter Langdon, and their five children. After an 1845 fire destroyed the existing house, the Langdons soon reconstructed another on the original site. After Walter died in the house in 1847, Dorothea left America, permanently settling in Europe by 1852, the year she gave (or perhaps sold) the house to her son, Walter Langdon, Jr. and his wife, Catherine Ludlow (née Livingston). Like later owners Frederick and Louise, they left no children and owned the house until their deaths, Catherine in 1883 and Walter Jr. in 1894.

After the Vanderbilts acquired the property, they attempted to update the existing picturesque Langdon House, however, the 1840s house proved structurally unsound, so they hired Beaux-Arts architect Charles F. McKim, of McKim, Mead, and White, to design a new house on the original site. McKim’s partner Stanford White, who was known as the artistic leader of the firm, assisted as an antiques buyer. The house, which has been described as a Beaux-Arts interpretation of the Italian Renaissance, was built with Indiana limestone and features large Greek ionic porticos on all four sides.

As the grounds were part of country estates owned by influential and wealthy families for nearly two centuries, the specimen trees which they planted may be ranked as a feature of interest second only to the house itself. More than 40 species and varieties are represented, many of them from Europe and Asia, including European ash, European beech, English elm, Norway spruce, Norway maple, the red-leaved Japanese maple, and a ginkgo, or Chinese maidenhair-tree. This ginkgo is among the largest of that species in the United States. Among the native American trees represented are sugar maple, flowering dogwood, eastern hemlock, Kentucky coffeetree, white oak, black oak, eastern white pine, and blue spruce. Other examples of their kind include large beeches, bur oak, and a great cucumber magnolia.

There are also extensive Italian Gardens, which lay south of the house, and date back as far back as 1795. Landscape architect James L. Greenleaf radically revised and enlarged the gardens between 1902 and 1903 for the Vanderbilts. The gardens, which incorporate several periods of development, were divided into three units: The greenhouse gardens, the cherry walk and pool gardens, and the rose garden. The first of these consisted of three separate parterre gardens within a rectangle framed on the west by the rose and palm houses and on the north by the tool house, carnation house, and gardener's cottage. The cherry walk and pool gardens, were located east of this group at a lower level, and progressed from the pergola to the garden house. The rose garden, still further east, had two terraces and contained panel beds.

Inside Hyde Park

The resulting 54-room house has a classic Beaux-Arts plan, with the major public rooms on its ground floor – the central Entrance Hall, Dining Room, and Living Room – all in one line, parallel to the Hudson River. North and South Foyers provide transitional space from the Hall to the Dining Room and Living Room. Five secondary spaces are located off the elliptical Entrance Hall: the Lobby, Den, Gold Room, Grand Staircase, and Lavatory.

First Floor

Courtesy National Park Service

The second floor rooms, comprising Mrs. Vanderbilt's suite of Bedroom, Boudoir and Bathroom (designed by Ogden Codman), Mr. Vanderbilt's Bedroom and Bathroom, Guest Bedrooms and Baths and the Linen Room, are disposed around the Second Floor Hall and the North and South Foyers. The third floor contains five additional guest bedrooms, and a Servants' Hall separated from the guests' rooms by a door at the main staircase. Supported by both concrete and steel, the Vanderbilt mansion was considered modern for its time. The mansion also included plumbing and forced hot air central heating and electric lighting which was powered by a hydroelectric plant built on the estate on the Crum Elbow stream.

Second Floor

Courtesy National Park Service

At least four fully fledged decorating firms were independently, and simultaneously, at work on the design and execution of Vanderbilt’s interiors under the general supervision of McKim and the clients. The firms were: Ogden Codman, A. H. Davenport, Georges A. Glaenzer, and Herter Brothers. The Vanderbilts gave McKim overall carte blanche on the design and furnishing of the ground floor reception rooms. Following an on-site conversation with McKim, Vanderbilt provided $50,000 at the disposal of Stanford White, excluding duty and freight charges, to spend on articles of furniture, preferably “old Italian,” and architectural salvage during an upcoming trip to Europe. Furnishing plans were provided for the hall, staircase, reception room, lobbies, dining room, living room and porticoes. In execution, the concept was followed with remarkable diligence. Herter Brothers would carry out the architectural decoration of the entrance vestibule, the elliptical hall and the dining room and A. H. Davenport, the living room. The balance of the ground floor was consigned to the French-born New York furniture dealer-decorator Georges Glaenzer.

In 1906, seven years after the house was completed, however, the Vanderbilts engaged New York architect Whitney Warren, of Warren & Wetmore, to redesign certain elements of the house. Warren, a close friend of his brother, William K. Vanderbilt, had recently taken over the design of Grand Central Station from Reed and Stem. In his redesign, he directed changes in the Entrance Hall and the Drawing Room, where he had the Harry Siddons Mowbray mural covered up (which the Vanderbilts did not like). On the second floor, he removed the coved laylight atop the second story and replaced it with a flat frosted glass laylight. The wood balustrade around the elliptical opening on the second floor was removed and replaced by a cast-stone balustrade. A deep plaster cove, embellished with lattice-work panels and oval medallions with female figures, was added to the ceiling of the second floor beneath the new laylight.

First Floor Rooms

Entrance Hall

The Entrance Hall provides immediate access to all of the principal rooms on the first floor. The elliptical room, though formal in appearance, functioned both as a living hall, used for informal gatherings, as well as circulation space, typical of classical French design. The room was furnished with tall palms, animal skin rugs, and comfortable couches, allowing for informal use where the Vanderbilts and their guests would sit down and fall asleep in front of a big fire.

The Hall is anchored by architectural features at each compass point—the main entrance centered on the east side, with a fireplace and mantel directly opposite on the west side. Located at the north and south ends of the ellipse, foyers connect the Hall with the Living Room and Dining Room. Angled alcoves flanking the fireplace provide access to the West Portico. Additional doorways open to adjoining rooms and the Grand Staircase. The walls are articulated with green marble pilasters with white marble bases and capitals. The ceiling reveals the second floor with an elongated octagonal opening encircled by a massive double balustrade, allowing natural light to flood the Hall from the laylight and skylight above.

Drawing Room

The Drawing Room (also called the Living Room) extends across the entire south end of the first floor. The wide, recessed doorway, flanked with antique Cippolino marble columns and fitted with large sliding pocket doors, connects the room to the South Foyer and the Hall beyond. Directly across the room is a wide doorway flanked by smaller doors leading to the South Portico. The composition of the ceiling visually divides the room into three bays, the effect enhanced by a pair of marble fireplaces and the arrangement of furniture into distinctive areas. The walls are paneled in Circassian walnut and the twin fireplaces are Italian marble.

Two large tapestries flanking the doorway are from a series depicting episodes of the Trojan War (the others from the set hang in the South Foyer). The east and west walls feature a pair of late 16th- or early 17th-century Italian armorial tapestries bearing the Medici family coat of arms. The room is furnished with a combination of antique Renaissance furnishings and Louis XV style seating. As it appears today, the room represents the design of Whitney Warren, who redecorated the room in 1906. The original ceiling mural by H. Siddon Mowbray was removed at that time.

Following dinner, men would remain in the Dining Room (or head to the Library) for cigars, while the ladies would retire to the Drawing Room for coffee and liquors. The men would later join them for games of cards, charades, and music.

Dining Room

The Dining Room extends across the entire north end of the first floor. Measuring 50 feet by 30 feet, the room is grand and spacious. The walls are finished with parcel-gilt full-height walnut paneling, rising to a 17th-century coffered ceiling salvaged from an Italian palazzo. The large stone fireplaces are from Paris and Florence. Carved in the 16th century, one illustrates scenes from the Judgement of Paris, and the other bears the Medici family coat of arms. The extension table at the center of the room seats up to eighteen.

The most important furnishing in the dining room is the large carpet—a rare Persian carpet — one of the largest Islamic carpets in existence measuring nearly 20 feet by 40 feet. Thought to be nearly 400 years old, this carpet was the single most valuable object in the house at the time it was installed, and likely remains so today.

The central panel of the ceiling was commissioned from the American artist Edward Simmons, who trained in Paris and was a leading figure of the American Impressionist movement. His surviving murals include those in the New York Supreme Court, the Waldorf Astoria New York, and the Library of Congress in Washington, DC.

Reception Room

Following her sister-in-law Alva Vanderbilt’s example, Louise installed an eighteenth-century-style French salon in the house known as the Reception Room (or the Gold Room). McKim had asked Stanford White in September 1897 to “Look up old room in Paris Style Louis XVI, and if you find anything worth while, cable,” for Hyde Park. While White was unable to produce the antique paneling, their decorator, Georges Glaenzer, recreated a richly-paneled Louis XV-style room inspired by French design sources.

The Reception Room, however, was used very little. Tea might be served there for very special guests during a weekend visit—or a small group of eight to ten dinner guests would congregate there until dinner was announced. It was more often used by Louise when she wanted to be alone, as a former butler explained that “when the door was closed that was a sure indication that Mrs. Vanderbilt did not want to be disturbed.”

Office

Vanderbilt’s office was off the Entrance Hall and directly next to the front door. The woodwork is Santo Domingo mahogany. Plates on the wall are Chinese, and a painting by the French artist, Lesrel, hangs over the desk. Above the fireplace, early Italian and Spanish flintlock pistols are grouped about an old Flemish clock. A hand carved Renaissance panel forms the back of the desk chair.

In the bookcase are about 400 volumes, mostly fiction and travel. Included among these are the college textbooks that Frederick used at Yale. From this room Vanderbilt conducted his estate affairs, such as tree culture and the operation of the greenhouses, gardens, and his dairy and stock farm across the road.

Library

The Library, sometimes called the Den, was also decorated by Georges Glaenzer. Swiss artists were brought to America to create the hand-carved wood on the walls. A vaulted section of the ceiling is molded plaster, made to simulate carved wood. The carved mantel of the fireplace reportedly from a European church. A porcelain clock-and-candelabra set on the mantel was a gift from Louise's mother. Guns on the wall opposite the fireplace are antique Swiss wheel locks. More than 900 volumes on history, literature, natural science, and other subjects fill the bookcases in the room. The Library was used as the family living room. In the afternoon, they gathered for tea there.

The Library (or Den)

Grand Staircase

The Grand Staircase, featuring sweeping wrought iron balustrade, begins with ten steps leading up to a landing along the west wall, followed by another ten steps to an east-facing landing, then ten more steps heading west to a third landing, and, lastly, nine steps east to reach the second floor. On the wall opposite the foot of the stairway is an 18th-century Flemish tapestry. The floor in the lower-stair hall is old Italian marble. A chair and marble fernery are Italian, and a large Chinese bowl of the Ming Dynasty is about 500 years old.

Italian busts and statues occupy niches along the way including marble sculptures depicting the infant Hercules (strangling one of the snakes sent by the goddess Hera to kill him in his cradle), Eros, Psyche, along with Persephone (Greek goddess of spring and queen of the underworld). At one of the landings is a painting by the French artist, Adrien Moreau. An early 18th-century Beauvais tapestry hangs on the second-floor wall.

Second and Third Floor Rooms

Second Floor Hall

In 1906, architect Whitney Warren installed the balustrade which now overlooks the reception hall. In the hall, there are three 18th-century Flemish tapestries, two Italian fringed and embroidered hangings draped over the balustrade, and two sets of matched high-backed chairs in walnut— one set of six chairs, one of four. A teakwood cabinet is of Chinese design.

View the the Second Floor Hall from the Vanderbilt’s rooms

North and South Foyer

In the North Foyer, on a Louis XVI table stands an incense burner fashioned of marble and cloisonne. Overhead is a chandelier of beaded crystal; one of similar design is in the south foyer. Hanging here are original paintings by the 19th-century artists, Schreyer, Bougereau, and Villegas. Vanderbilt was more noted for the fine tapestries he collected than for outstanding paintings.

The South Foyer leads to the master bedrooms. French doors can be closed to separate this wing from the rest of the second floor. In the foyer are paintings by Kellar-Reutlingen and Firman-Girard.

Mrs. Vanderbilt's Room

Mrs. Vanderbilt's suite of rooms are decorated in the Louis XV style, with references to some of the finest rooms created in eighteenth-century France. The railing around the bed is borrowed from an architectural convention typically found in royal bed chambers. For the architecture of the room, Ogden Codman relied on 18th-century architectural platebooks by Jacques-François Blondel and Alexandre Eugene Prignot. The British art dealer, Joseph Duveen, procured the 15 painted vignettes—copies after Charles-Joseph Natoire and Francois Boucher.

The heavily napped rug was made especially for this room and weighs 2,300 pounds.

Notable furnishings from the workshop of French ébéniste Paul Sormani fill the room, including a curvaceous commode in the Louis XV style made about 1875. The floral inlay and marquetry, and the gilt bronze mounts are indicative of Sormani's ability to create a impressive furniture in the style of the furniture made for French royalty.

Adjoining the bedroom is the boudoir, furnished in the same motif. Notable pieces include a Dresden chandelier-and candelabra set.

Mr. Vanderbilt’s Room

Georges Glaenzer also contributed to Frederick’s bedroom on the second floor. The room has carved woodwork of Circassian walnut. The bed and dresser were designed as part of the woodwork and were installed by Norcross Brothers. Although later slightly modified by the Herter Brothers, the bedroom as designed by Glaenzer featured Verdure tapestry wall hangings. The walls and doors are covered with 17th-century Flemish tapestry. Hand-painted designs on the silk lampshades match those on the Chinese bases. The fireplace has a large carved mantel. On the floors are dark-red rugs made in India.

Much of the French classical bedroom furniture in Hyde Park, thought to have been supplied by Glaenzer, might be from his subcontractor, A.H. Davenport, rather than French sources. The suites bear close resemblance to the Davenport-supplied French Louis XV and Louis XVI style bedroom suites ordered by Ogden Codman for Frederick’s elder brother, Cornelius Vanderbilt II, at The Breakers in Newport and now known to have been primarily manufactured by Davenport.

Guest Rooms

The Blue Room is the largest of the guest rooms. Mrs. Vanderbilt’s niece, Margaret “Daisy” Louise (née Post) Van Alen, used this room during her visits to the Vanderbilts. The windows of this room give a sprawling view of the Hudson and the mountains beyond. A white onyx French clock and companion pieces adorn the mantel, and a rare old (Ghiordes) prayer rug is spread before the fireplace.

In the Mavuve Room, most of the furnishings are of French design. In the center of the room is a finely woven Persian dower rug. Pieces on the mantel are of the French Empire period.

The Red Rooms open onto the second floor hall and are connected by a doorway to form a two-room suite. As with the other guest rooms, the furnishings are in the French style. A frieze on a Greek subject embellishes the 18th-century English Georgian mantel in the larger room.

Common to all guestrooms is the 18th-century French style of furniture and the use of a distinct color scheme. The guestrooms are believed to reflect the design of Ogden Codman Jr. Each guestroom has a bath and one or more closets. The bathroom accessories always matched the color scheme of the guestroom.

Third Floor Rooms

On the third floor, there are five further guest rooms, separated from the servant's hall and their quarters. The third floor guestrooms are as elaborate as any on the second floor and consist of the Pink Room, with white painted furniture—often used by Vanderbilt in the winter; the Little Mauve Room, furnished with oak furniture; the Empire Room, with French Empire period furniture and satin-covered walls to match the covering on the furniture and bed; and the White Room, with white furniture, drapes, and upholstery. When the nine guestrooms in the house could not accommodate everyone present, the pavilion was used as a guesthouse.

End of the Vanderbilt Era

After Louise’s death in 1926, Frederick became a virtual recluse; living with the servants on the third floor until his death in the home in June 1938. Reportedly the only Vanderbilt of his generation to increase his inheritance to a sizable fortune, he was a director of 22 railroads at the time of his death, including the New York Central, his family’s primary source of wealth, where he had been a director for 61 years.

Like the Langdon’s before them, the Vanderbilt’s left no children to inherit their estate, so Frederick left Hyde Park (amongst others) and $10 million to his wife's niece, Margaret “Daisy” Louise (née Post) Van Alen, the widow of James Laurens Van Alen (a grandson of The Mrs. Astor) who later married yachtsman Louis Bruguière. Having no need for Hyde Park, she put it on the market, but in the midst of the depression, there were no takers.

Vanderbilt’s neighbor down the Hudson River, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, became interested in preserving the estate, citing its collection of trees, and his influence was a major factor in having the park portion of the estate, including the house (together with most of its original furnishings), donated and transferred to the National Park Service by Van Alen. The acquisition was approved in 1939, and in July 1940, the property was opened to the public under its current name, the Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site.